For my blog this week here is an article I wrote some years ago for the school magazine. The article concerns perhaps OLA’s most illustrious former pupil, in whose honour the Senior School library is named. He was a gallant and daring officer whose devotion to his old school was unwavering.

There is little doubt that Captain Bertram Louis Ratcliffe MC was one of the most remarkable pupils ever to attend what, in later times, was to become Our Lady’s Abingdon. The episode for which he is mainly known is his dramatic escape from a train in northern Germany as a prisoner of war during the First World War, but there is much more to Ratcliffe than this. As well as being a career soldier he was at various times an actor, writer, businessman and benefactor of his old school, dying at the ripe old age of ninety-eight in 1992. His uncle was the great industrialist Lord Brotherton, who himself was a major benefactor of the library at Leeds University that bears his name and in whose collections Ratcliffe’s papers and memorabilia are now gathered. Many of Ratcliffe’s books, including an account of the early life of Napoleon Bonaparte, are still available and provide a fascinating insight into the interests that preoccupied him from the period immediately after the Great War right up to his death. His 1935 novel ‘Idle Warriors’ gives a more or less faithful account of his experiences during the defining period of his life, his three year imprisonment at a camp for officers near the Bavarian town of Ingolstadt.

Ratcliffe was born on 8th March 1893 in what was then the prosperous London suburb of Upton Park, West Ham, an area that had recently been developed as a desirable residential district for employees of the City of London. Ratcliffe’s parents, both Roman Catholics, moved there from their original home in Manchester some time before the birth of their youngest son, perhaps attracted by West Ham’s status as a growing centre of Catholicism with its newly built and impressive church of St Antony of Padua. According to the Census record, by 1901 Ratcliffe’s mother had moved to Hornsey in Middlesex, while his father appears to have emigrated to Australia.

A year later young ‘Bertie’ was sent away to Abingdon to board at St. Joseph’s, the preparatory school founded by the Sisters of Mercy in 1883 as a sister establishment to Our Lady’s, the girls’ convent school they had started in the early 1860s. The boys’ school prepared its pupils for the major Catholic public schools such as Downside, Douai and Ampleforth although this was not the route that Ratcliffe was to follow. He remained as a pupil until 1905, saying later in life that it was the only school he attended where he was truly happy. His affection for the school is shown by his many benefactions to it in later years and his frequent visits to events such as the annual Prizegiving.

In the summer of 1907 Ratcliffe started as a boarder in the Head Master’s House at Harrow School, where he was to remain until 1912.

After leaving Harrow, he became an officer cadet at the Royal Military College Sandhurst, from where he passed out in July 1913 with a commission in the 14th the Prince of Wales’ Own West Yorkshire Regiment. Not much more than a year later he was to be caught up in the general mobilisation that occurred as the British Expeditionary Force was formed to cross the Channel and prosecute the war against Germany. At 6.15 am on 7th September 1914, along with the officers and 959 men of the regiment’s 1st Battalion, he left Southampton for France on the troop ship Cawdor Castle and by 16th September had reached the Aisne River. This was the period in the war following the Allied victory at the Battle of the Marne, but by the middle of September the Germans had begun a counter-attack. The British line was being heavily bombarded as, on the 19th of the month and in heavy rain, Ratcliffe’s Battalion replaced the Coldstream Guards on the heights of Craonne. Here they held the extreme right of the British line, with the Fifth French Army to their flank. Enemy snipers opened up before they were properly dug in, but they worked on trenches through the night and were able to stand to arms at 3.30 am. These were the very earliest days of the trench warfare that was later to become the defining feature of the Western Front. At 5.00 am the Germans launched a heavy infantry attack on the French who, having suffered heavy casualties, withdrew. Just over an hour later the incident occurred that Ratcliffe later used for the opening lines of ‘Idle Warriors’:

‘Possibly it was the blade of my raised sword that, glinting in the rays of the morning sun, drew the marksman’s bullet. I saw him fling himself upon the ground and take aim, and I pointed my sword at him and at the little groups of grey men that were appearing from among the trees and making alternate rushes towards us down the green slopes. I was not afraid; for there is courage in ignorance, and I was barely twenty years old. Suddenly a mailed fist struck my right shoulder; an electric shock passed through my body; my sword spun from my hand: I was falling dizzily as one falls in a dream … down, down at ever increasing speed. Then I found that I had stopped, and, to my astonishment, that I had only reached the bottom of the half-dug pit in which I had been standing a moment before. Blood filled my mouth and a hot stream was spreading over my back.’

Across the day the 1st Battalion suffered heavy casualties and, by its end, only 5 officers and 250 men remained. Seven officers were killed, two were wounded and eight were counted as missing: Ratcliffe, who had been taken prisoner by the Germans at 2.00 pm, was one of these. Unable to walk, he was placed on a cart and by 23rd September found himself in the town of Laon. Throughout this time his wound had remained undressed and he had received no medical attention. Under French administration, he was lodged in the Lycée with a number of other captured British and French officers and here he describes himself as being well looked after by a French doctor. His wound received attention and he was moved, on 8th October, to the Palais de Justice in the same town. Finally, on 10th October, he was packed into a fourth class train carriage along with twenty-four German soldiers and, passing through Cologne and Frankfurt, travelled south.

Five days later, the train arrived at Ingolstadt in Bavaria. Here, along with six French officers, he was made to walk ten kilometres to Fort X, one of a ring of forts that had been built around the town by its Bavarian rulers as a redoubt in the nineteenth century. In ‘Idle Warriors’, Fort X is given the name Fort Prinz Heinrich and here, in rather lurid terms, Ratcliffe describes his introduction to what was to be his home for the foreseeable future. ‘I seemed to have travelled far, not only by road and rail, but through time as well. Fort Prinz Heinrich? The great gates swinging on dusty hinges; the screeching bolts; the moat; the piled-up cannon balls; the sentries half seen in the lantern rays; the colossal figure of the commandant; the evil glint in the eye of his secretary, Muller; the sickening blow from the sentry’s rifle.’

In the interview he gave to the British military authorities on his return to England in April 1917, Ratcliffe described the camp and his experiences there in more detail: ‘The fort is surrounded by a moat; all the windows are barred, and the entrance is by means of a tunnel. All the rooms are underground; regular casemates. I was placed in a room with five French officers; we each had a bed, straw mattresses, one sheet, a straw pillow, two blankets, and a stool issued to us. In the room there was also a small table, large enough to accommodate four, at which we had to eat all our meals … The guards, as a rule, were respectful. We had two roll-calls a day, at 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., and were allowed out until 7 p.m.’ Of the 3,000 or so men at Ingolstadt, only twenty-five were British. Here Ratcliffe remained until 19th April 1915, when he was allowed to go to the military hospital at Ingolstadt for an operation on his right arm, which had been useless since he had been wounded. After the operation, conducted by a nerve specialist named Dr. Funroeher, he regained the use of the arm and was allowed to convalesce for two months.

In April 1916 Ratcliffe was transferred to another of Ingolstadt’s military prisons, Fort VIII, which he describes as more comfortable than his former billet. Throughout his time as a prisoner of war he is conscious of his duty to escape, but the fort’s location in Bavaria made a successful breakout almost an impossibility. Prisoners at the various Ingolstadt forts did try to get away, but the vast majority were recaptured and sometimes transferred to the notorious Fort IX, reserved for really difficult cases. The future General de Gaulle, to be encountered by Ratcliffe in the Second World War, spent some time here after making himself too troublesome to his captors. Ratcliffe himself got into trouble when, in May 1916, he was put in the cells for a week after a map of Bavaria was found in his luggage. The opportunity that was to lead to his escape only came nearly a year later in early April 1917, when he and a number of other British officers were told that they were to be transferred to a new camp in the north western corner of Germany at Krefeld.

Their journey, under armed guard, began on April 6th when they were put on a train travelling to Cologne via Würzburg. The train arrived at Cologne at 5.30 pm on the afternoon of the 7th from where, after a change of trains, Ratcliffe and his fellow prisoners set off again an hour later. In his London interview he recalled the next dramatic steps in surprisingly matter of fact terms: ‘The journey continued, and at about 8 p.m. we arrived at a small junction 2 kilometres south of Crefeld. It being dusk, we five {British officers} left the train as it was drawing out of the station, ran a short way along the line until we came to a crossing, where we divided into three groups.’ In ‘Idle Warriors’ he gave this same episode, the beginning of his daring escape, the value it deserved:

‘Half an hour went by. We were travelling fast and jagged blocks of stone, strewn along the embankment, did not encourage that vital leap. Another ten minutes went by, another five. Featherstone {the name Ratcliffe gives to his fellow escapee, Squadron Commander Briggs} and I searched one another’s eyes. It was time to act. Suddenly the Bavarian officer appeared in the doorway. “In a few minutes we shall be at our destination. You will please prepare your things.”

Then, as he turned away, the opportunity came: it could have come at no better time or place; for the light was fading, and the line was running nearer to the frontier than it had done throughout the journey. The train began to slow up, giving us, as it were, a sign, and putting my head out of the window I had a swift vision of troops leaning from the train and waving to women in houses besides the line; …Wildly I wrenched at the handle. Why wouldn’t it turn? Damn the thing. Featherstone’s voice was at my ear, impatient, tense: “Quick, for God’s sake … open the bloody door … open it … Hell!”

The handle gave, the door flew open and I leapt, or rather fell out, bounced helplessly, turned head over heels, picked myself up and started to run. Beside me I felt rather than saw Featherstone, running and breathing heavily. Well, we had done it now, we had plunged … and the train was already out of sight.’

Briggs and Ratcliffe had on them only a map and a compass, now in the Liddle Collection at Leeds University, and some chocolate. They were dressed in full British uniform, Ratcliffe in a knee length coat and puttees. Once off the train they were soon spotted by two men and had to run across some ploughed fields to get away from them: ‘We kept on walking until 4.30 am the following morning, never touching the roads, always going across ploughed fields; then we hid in a small wood by the side of the road until 8.30 p.m., when we started off again on our journey, across more marshes and on until midnight, when we struck into a very big forest, walked for one and a half hours through the forest until we suddenly struck a sentry.’

At this point Ratcliffe and Briggs separated, Ratcliffe being pursued by the sentry until he managed to evade him by lying low in a ditch. At around 2.00 a.m. he set off again and soon saw the line of barbed wire that marked the border with Holland. Unfortunately, he was immediately spotted by another German soldier. ‘I started to run as hard as I could over the frontier, but I had only done about four paces when I caught my foot in a furze bush and fell. The sentry followed me, and when I got up he was standing 2 yards from me.’

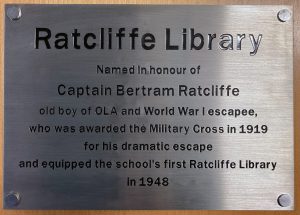

The two men now had a conversation in the moonlight, at the conclusion of which Ratcliffe bribed the sentry for 25 marks to let him go. He was then allowed to make a dash for the border, finally arriving in Holland at 5.30 a.m. on the morning of April 9th. Eventually, after reporting to the police and proceeding via Venlo and Rotterdam, he was handed over to the British Consul and by April 12th was back in London. On this day he sent a telegram to relatives in Yorkshire saying that he had escaped and the interview quoted from above took place at his brother Edward’s home in Ealing. This interview, now lodged in the National Archives at Kew, is the main source for the information we have about Ratcliffe’s prison experiences, the details of which were fleshed out so dramatically in ‘Idle Warriors’ eighteen years later. On 18th April King George V invited Ratcliffe, who by this time was staying in Yorkshire, to come back to London to tell him about his escape, an event which duly took place at a lunch at Windsor Castle on the 23rd. For his brave exploits he was awarded the Military Cross.

The later events of Ratcliffe’s long life are also of great interest and will one day provide rich material for a biographer. He spent the period from 1917-19 as ADC to Major-General Sir P. C. Palin in Palestine, retiring from the Army in 1920. In 1924 he married the Belgian pianist, Andrée Marie-Helene Vauthier, and in the Second World War was appointed staff captain on the British military mission to General de Gaulle and the Free French. The dustcover of his 1981 account of the early life of Napoleon gives the following information about how he occupied his time when not serving his country: ‘After the war he took up an apprenticeship with a merchant firm in the City before establishing his own company importing Scandinavian products. He then became a director and later chairman of an industrial chemical firm. After a short period as a professional actor he took up two further chairmanships … before devoting his time to writing.’

In addition he became a benefactor of his old school in Abingdon, giving a large sum in 1948 to equip the school library that was named after him. He also donated money to fund an annual Ratcliffe History Prize and the Hilaire Belloc Prize, for which he sought and gained the consent of Belloc himself. Ratcliffe was a regular attender of the annual Prizegiving and donated other items to the school, such as footballs and boxing gloves. He also contributed poems to the school magazine.

It is fitting to end by citing the motto of Bertram Ratcliffe’s old regiment, the West Yorkshires: ‘nec aspera terrent’. The harshness of war held no fear for this former pupil of the Sisters of Mercy and, as we continue to commemorate the centenary of the First World War, it is appropriate once again to recall his name.